By Aizat Shamsuddin

Aizat Shamsuddin is a security analyst and practitioner focusing on the nexus between crime and ideology in the contexts of Malaysia and Muslim-majority countries.

Recent episodes of violence and harassment on KK Mart franchises such as in Kuching, Kuantan, Bidor, and Batu Pahat, spurred by a nationwide boycott campaign due to alleged blasphemy involving 14 pairs of socks printed with the word “Allah” and imported from China, underscore the influence of domestic political extremism in Malaysia.

In multi-racial and multi-religious societies such as Malaysia, safeguarding religious communities against provocations is essential for preserving social harmony, peace, and security—key pillars underpinning social cohesion and economic stability. Nonetheless, these protective efforts must conform to the rule of law. Resorting to violence and harassment, as exemplified by the KK Mart incidents, is categorically unacceptable.

The KK Mart incidents highlight a broader issue of political extremism impacting businesses in Malaysia. The #BuyMuslimFirst campaign, initiated in 2018, has been exploited by far-right factions to delegitimise products owned by non-Muslims, even if they are halal-certified. In 2023, Zus Coffee faced a boycott due to its logo resembling a Greek deity. Additionally, vigilante efforts have sought to restrict the sale of alcoholic beverages in Malay-Muslim majority areas, as seen in Manjoi, Perak, in 2018, and at Jaya Grocer in Puncak Alam, in 2020. In a separate 2023 incident, a vigilante complaint against international brand Swatch for selling LGBT-themed watches prompted a raid and a ban by Malaysian authorities. While consumer boycotts fall within legal rights, they should align with ethics and social justice, targeting businesses implicated in unethical practices like forced and child labour or war crimes, rather than being fuelled by racism and misinformation.

Recent boycotts targeting KK Mart franchises as well as Starbucks and McDonald’s, spurred by calls to boycott businesses linked to Israel following the Israel-Palestine conflict after October 7, have led to significant spillover impact. Vigilantes have launched premeditated arson attacks, harming ground staff, including young working-class Malays, and causing extensive damage to these businesses’ properties. Moreover, the boycott against KK Mart has prompted threats against other establishments, such as ‘99 Speedmart‘ and Kuala Kedah Fresh Mart, dubbed ‘KK Fresh Mart.’

Additionally, Bumiputera figures who have called for de-escalation following the KK Mart incidents, like Ameer Ali bin Mydin and Khairy Jamaluddin have encountered backlash. Meanwhile, Penang Mufti, Datuk Seri Wan Salim Wan Mohd Noor and Bukit Aman Criminal Investigation Department Director, Shuhaily Zain have issued warnings against public overreaction.

The Initiative to Promote Tolerance and Prevent Violence (INITIATE.MY) has observed a marked increase in interethnic tensions since 2018 following the rise of Pakatan Harapan (PH) and its Chinese-dominated party component, the Democratic Action Party (DAP).

Post-2018 period has seen an uptick in rallies, boycott campaigns, and crimes targeting ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities, as well as human rights defenders—fuelled by dynamics extending beyond usual catalysts such as elections and court controversies.

The rise of PH has been viewed as a challenge to the Malay-Muslim dominance. In reaction, Malay-Muslim political alliances, primarily dominated by the Malaysian Islamist Party (PAS) encompassing Muafakat Nasional (MN) from 2019 to 2022, and Pakatan Nasional (PN) from 2020 onwards, along with disgruntled factions within the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and other far-right networks, have redoubled their commitment to cementing a more aggressive Malay-Muslim hegemony.

Three trend analyses of far-right responses on KK Mart’s case:

First, far-right groups persist in undermining trust in democratic institutions and the government, advocating for radical measures beyond Malaysia’s stringent anti-blasphemy laws in both civil and Sharia realms. Numerous influential figures, including UMNO Youth Chief, Muhamad Akmal Saleh have disseminated content that fuels anger and advocates for aggressive actions. Despite government prosecutions of KK Mart’s top executives and those responsible for perceived blasphemy, these actors deem such actions insufficient. Furthermore, distrust in the state was exacerbated during this period by calls from over 70 NGOs for inaction against Muslim preachers insulting other religions. Far-right groups view non-violent responses, such as KK Mart’s public apologies and dialogue attempts, as ineffective, thereby pushing public sentiment towards extra-legal measures, including harassment and violence.

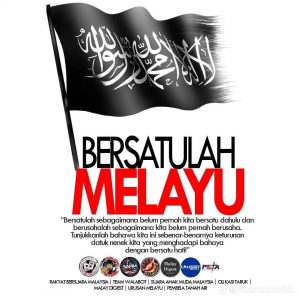

Secondly, social media and messaging platforms significantly intensify offline harassment and violence. The widespread dissemination of the Prophet’s Hadith, calling for the execution of blasphemers without providing context, escalates hostility. Besides, the co-option of the controversial ar-Rayah banner continues to be seen in the boycott expressions (see images below). Not to mention, Akmal Saleh received death threats for his aggressive incitement with impunity. Influential figures often exploit these platforms to spread fear-mongering and jihad-inciting narratives, aiming to secure Malay support and gain benefits for their business and political allies, all while generating online revenue from the spread of such content.

Thirdly, offline threats are becoming more common in the context of race and religion disputes. In the KK Mart incidents, vigilantes, radicalised by the politicisation of race and religion, employed improvised explosive devices (IEDs), such as Molotov cocktails and petrol bombs on their targets. A similar tactic was observed following the Kalimah Allah court decision in 2009, resulting in multiple attacks on churches and a Sikh temple in early 2010 throughout Malaysia. The simplicity of manufacturing IEDs, aided by the accessibility of online tutorials and explosive materials, represents a substantial security concern.

In response to these developments, the Malaysian government must take decisive action to ensure that extremist actors instigating dangerous narratives and violence are brought to justice. Neglecting to hold such instigators accountable will continue to fuel grievance within the predominantly peaceful Malaysian population. Furthermore, Anwar Ibrahim’s Madani government and the religious bureaucrats must adopt a more moderate approach, positioning themselves as peacebuilders to avert further division and the normalisation of violence. Without concerted efforts to de-escalate tensions, this vicious climate could further compromise the safety and stability of both society and the economy.

For the business community, actively engaging in anti-extremism discourse and measures is crucial. Firms must integrate security risk assessments into their strategic planning to protect their employees from reprisals by extremist actors. Since 9/11, large multinational corporations have implemented security assessments to mitigate terrorist and geopolitical threats. Yet, domestic extremist threats have been undervalued, a perception that must change. The business community should work in partnership with the government and civil society to foster social resilience, investing in a sustainable solution to address the threats of dangerous political ideologies and movements.